Reach the Roof of Africa, Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,341’), on this high-altitude Tanzanian adventure, on the easiest non-technical climb of the world’s Seven Summits. Expect to spend 6-7 days hiking on the Rongai route.

Overview: 6 days, 43.8 miles, 12,945 ft. elevation gain

Kilimanjaro is the highest free-standing mountain in the world since it stands alone from any mountain range, making its size and height all the more impressive. Because of its reputation, ease of accessibility, and Tanzania’s affordability, this is an incredibly popular mountain to climb and therefore laden with lots of red tape. It is required to organize this climb through a licensed mountain operator, as well as follow one of the official climbing routes – so be sure to do your due diligence and research the right route for you!

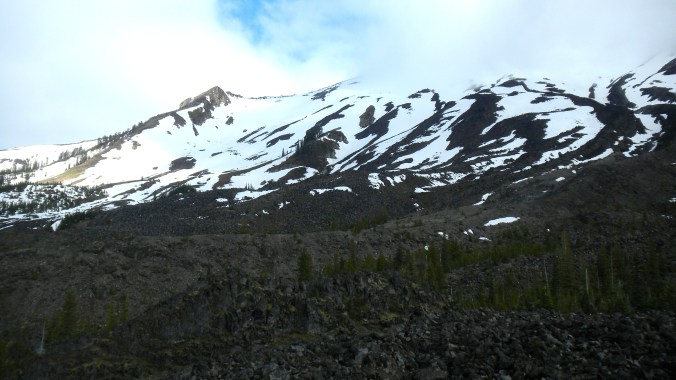

The Rongai Route is one of the least traveled ways up Africa’s tallest peak, allowing a more remote hiking experience. Unlike the southern routes, Rongai is a moorland or high-altitude desert climate, with far less precipitation than rainforest routes. The Rongai route meets the Marangu route on the final night to follow this trail to the summit.

Most, if not all, of the routes up the mountain begin in the town of Arusha, Tanzania, accessed by the Kilimanjaro International Airport (JRO). For this particular itinerary, you’ll head to the northeastern side of the mountain along the border of Kenya, about a five hour drive from Arusha. Expect to spend 6-7 days hiking on the Rongai route.

Day 1: Nale Moru (1,950 m/6,400 ft.) + Simba Camp (2,650 m/8,700 ft.)

- Walking distance: 6.5km/4 miles

- Elevation gain: 700m/2,300 ft.

Today is the start of it all, beginning at the Rongai Gate in Nale Moru. After registering with park officials and finalizing the last of your packing, your hike starts through fields and a few small villages. You’ll spend the night at Simba Camp, close to the First Cave, overlooking the Kenyan plains.

Day 2: Kikelewa Caves (3,600 m/11,810 ft.)

- Walking distance: 9 km/5.6 miles

- Elevation gain: 950m/3,110 ft.

On the second day, vegetation grows thinner and you’ll enter into a truly high-alpine desert biosphere. Pass by the Second Cave (where you might stop for lunch) and end your day at Kikelewa Camp, next to the Kikelewa Cave.

Day 3: Mawenzi Tarn (4,330m/14,210 ft.)

- Walking distance: 6km/3.7 miles

- Elevation gain: 730m/2,400 ft.

As the week progresses, your days grow shorter, and this hike to Mawenzi Tarn should only take a couple hours as your body adjusts to the higher elevations. This is when proper hydration and a slow pace (pole, pole, as the Tanzanians would say) play a huge part in your successful acclimatization. You’ll spend this night at Mawenzi Tarn and have plenty of time in the afternoon to explore the plains and rocky outcrops in this vast area.

Day 4: Kibo Huts (4,330 m/15,420 ft.)

- Walking distance: 9km/5.6 miles

- Elevation gain: 370m/1,215 ft.

This is the point where the Rongai Route meets up with the Marangu Route for your final summit push. You’ll want to leave Mawenzi Tarn early this morning so that you have plenty of time to rest and prepare for your summit bid later in the night. The Kibo Huts are a little like a semi-permanent village, with huge crowds from both routes and plenty of noise and excitement.

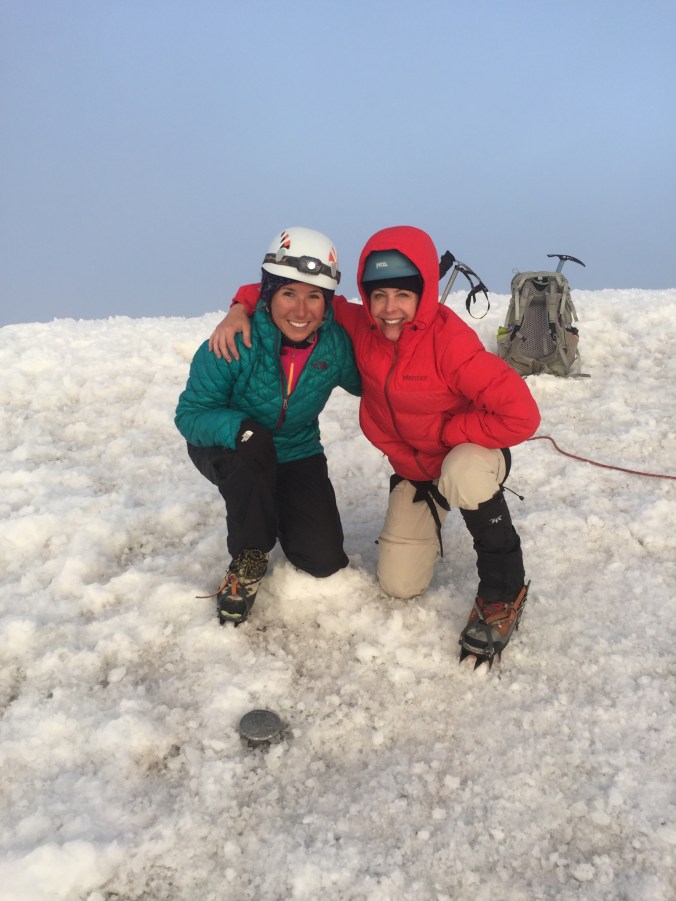

Dancing at the summit of Uhuru Peak, Kilimanjaro.

Day 5: Summit via Gilman’s Point to Uhuru Peak (5,895m/19,340 ft.) to Horombo Huts (3,700m/12,200 ft.)

- Walking distance: 5km/3.1 miles ascent + 15km/9.3 miles descent

- Elevation gain: 1,195m/3,920 ft.

- Elevation loss: 2,195m/7,200 ft.

Day 5 begins late night of Day 4, waking, eating, and heading out of camp by midnight for your summit bid. The first half of your early-morning leading up to Gilman’s Point (5,700m/18,700 ft.) will be full of undulating switchbacks that may be made more brutal by biting cold and harsh winds, as we were. From Gilman’s Point you’ll get to look into the huge volcanic crater and surrounding ice caps, with the true summit just ahead. The crater rim to your left leads you all the way to Uhuru Peak with the famous summit sign of Kilimanjaro.

Unfortunately this last push is where hikers are most likely to feel the full affects of altitude sickness, and we saw lots of folks being ushered or even carried down the mountain at this point. That’s why it’s all the more important to limit your time at the top and descend quickly, back to the Kibo Huts for some fuel and a short break, before you’ll continue on to the Horombo Huts.

Day 6: Marangu Gate (1,860m/6,102 ft.)

- Walking distance: 20km/12.5 miles

- Elevation loss: 1,840m/6,040 ft.

After all of the climbing you’ve accomplished, this hike out should feel like a piece of cake. Descending on the southside, you’ll be immersed in a beautiful rainforest as well as the infamous crowds you avoided to the north heading up for their chance at the summit. Take your time, enjoy the scenery, and give yourself a huge high-five once you’ve reached the final Marangu Gate.

The final crater rim walk up to Uhuru Peak from Gilman’s Point.

While this climb is truly non-technical and often described as “easy” or a simple “walk-up,” proper planning and packing is essential to any climber’s success. Freak weather storms, freezing temperatures, and debilitating altitude sickness can occur at any time without warning. Pack for everything, and be prepared for anything.

Packing List

- Wool hat + sun hat

- Sunglasses

- Sunscreen, +SPF chapstick

- Heavyweight gloves

- 3+ upper body layers – shirts, fleece, long underwear

- Hardshell rain jacket

- Down jacket

- 2+ lower body layers – trekking pants, long underwear

- Hardshell waterproof pants

- Gaiters

- 6+ pairs wool socks

- Sturdy hiking boots

- Trekking poles

- Headlamp + extra batteries

- 40+ liter backpack

- Sleeping bag + sleeping pad

- 2+ liter water bottles

- Iodine or other water treatment

- First aid kit

- Deck of cards, journal, or charming humor for afternoons spent acclimatizing at camp